The Oley Hills site actually consists of three separate sites spread out along a north-south ridge about 900 feet high in Berks County, Pennsylvania. As with most sites in the Northeast, these are characterized by a mixture of Colonial and American Indian stonework, and the problem is trying to distinguish the two. For the Central Ridge site, which is the most impressive visually along the entire ridge, the focus on the large tor or boulder on the summit and the fact that quartz found incorporated in some features had to have come from a location in the valley below and not on the ridge, separates discussion of this site and the features on it away from any colonial interpretation.

Two other sites along the ridge are different visually and in the types of features than the Central Ridge site, yet they appear to have little connection with any type of agricultural purpose. The Row-Linked Boulders site at the south end of the ridge has been briefly discussed in a web article I wrote and is here the subject of a more fully rounded article, since when that first article was written nearly ten years ago, I was just beginning my study of Indian stonework, and now I have much more information under my belt, so to speak, and can look at it with a fresh vision.

With any lithic site that one studies, one must try to see and understand what makes it different and distinctive from surrounding stonework, assuming the latter to be Colonial, such as walls. How would one describe the terrain the stonework is constructed on? What is its geology? And how does the stonework one is attracted to emphasize the geology and geological processes? It is this latter point that seems to distinguish Indian stonework from Colonial. Colonial farmers constructed walls to enclose fields and mark property boundaries. Indian stonework on the other hand, such as walls or rows is often entirely different in that it emphasizes and connects boulders that have that elusive quality called "presence", be it their size, shape or location, or that have been subjected to geological processes, such as splitting. These qualities are found in the Row-Linked Boulders site.

Philip Smith's long article "Aboriginal Stone Constructions in the Southern Piedmont" made a deep impression on me when I was first starting out on my study of Indian stonework in the Northeast, as I felt that what he described in Georgia and elsewhere in the South would find resonance in the North. When he wrote the following: "one of the most striking features is the apparently deliberate purposefulness by which large boulders and outcrops were tied in with the walls. In some cases the walls seem to make deliberate detours to link themselves with the larger rocks."" (Smith 1962: 34-35), I felt he was describing this small site in eastern Pennsylvania. It was this connection that stimulated and encouraged me with the research.

The site is about a quarter mile south of the Central Ridge site at the very end of the ridge. In 1998, John Waltz, a good friend who helped me map the Oley Hills site, decided at one point to check what else could be found south of the Central Ridge site, and so he went off on his own to see what he could find. After about an hour he returned to let me know that he had found some interesting stonework, and he wanted to show it to me.

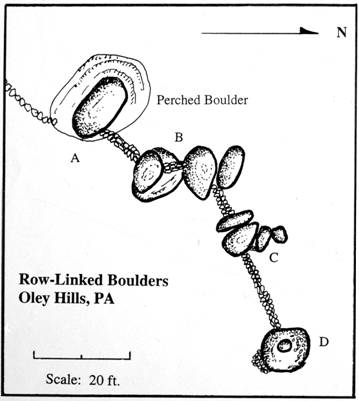

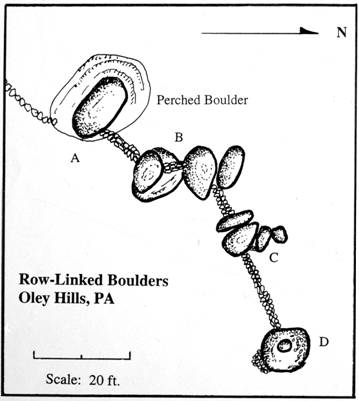

We walked through some dense tangles of vines and brush and eventually reached this small site, no more than 80 feet long from one end to the other (Fig. 1)

This small site, as with the Central Ridge site to the north, has as its central focus a tor, which in this instance is a large free-standing boulder perched on a rock outcrop (Fig. 2).

As I pointed out when discussing the Central Ridge site, the last glacial episode, the Wisconsin, ended its southern movement some twenty miles to the north, and so any large boulder found below this zone cannot have been carried here by the glacier, but instead must have eroded in place. This is the explanation for the boulder pictured in Figure 2. It has exactly the same lithology as the bedrock on which it rests. The two belong together, yet they are separate.

Looking at the site from below and a bit further south, which is how I have usually approached it, presents a very inviting scene (Fig. 3), with a stone wall meandering up the slope to end just before engaging the large boulder on the rock outcrop at the top center. This boulder measures 12 feet long by 5 feet wide by 3 feet thick, and underneath the east facing overhang is a cluster of small fist-size stones, what William Sevon, a former Pennsylvania State Geologist, said were not spalls from the underside of the boulder, but were stones that had been placed there deliberately. In other words, they were donation stones, not unlike votive objects that were often placed at a shrine in classical times, perhaps to ensure good health or good luck from the gods.

If we use the map (Fig. 1) as a guide, we progress from the boulder or tor (feature A) to the next feature nearby (B), which is connected to the tor by a short stone wall or row.

Here we find a carefully laid U-shaped stone fill between two boulders about 3 feet above ground level. It is not a wall by any stretch of the imagination, but simply a fill that symbolically connects two boulders and also forms a visual link to the entire boulder complex, tying everything together. In certain respects, it is not unlike the V-shaped fill found at the Terraced Boulders site only a hundred or so yards northeast of this site, or a similar one in South Newfane, Vermont.

This area and particularly the cluster at point C is characterized by a number of frost split boulders that have broken apart in odd ways, creating a landscape that is very strange looking and sometimes appears even sinister, particularly on dim cloudy days. We get a sense of this by looking back on it from the north end of the site (Fig. 5), with a large boulder with a rocking stone on top to the right, and in the immediate distance to the left is a pointed boulder that looks like a tooth. The site has a lot of spiritual energy, and it was undoubtedly this characteristic plus the presence of the tor that attracted the Indians to it.

We get some sense of the geological turmoil that occurred at the site long ago by examining the area near Feature C. Looking at it from the west we find a cluster of three large boulders, which one might call the Three Sisters. The one on the far right is the

snaggle-toothed boulder shown in the distance in Figure 5, but here it is viewed from the back. It was formerly part of the larger boulder in the center -- actually part of its top. But at some point in the past it separated, slid off to the right and ended up more or less upright, resting against the side of the large boulder. Visible from the other side are two angular stone that bridge the gap between the two halves.

The one nearest to us was once attached to the center boulder, but it too slid off and is now resting against the parent boulder. Looking at it from the side, a bit to the north, we see something very interesting: a short section of cobble-like stones filling the inverted V-shaped gap between the boulders and symbolically connecting the parent boulder to the left with the section that broke off. Some might conclude that this is nothing but a small animal cubby, but it makes no sense as an animal trap. My own conclusion is that this short wall or fill and the features it touches enables us to get close to the idea behind the stonework, in that the individual who saw this had no geological explanation for it; to him, everything was animated, and there was a spiritual explanation for what he saw. The split boulder symbolized the power or spirit that was once present in it and which had been released. The construction of the fill could have been a way of appeasing the spirit contained in the rock, of connecting with the power (or reconnecting with the power that was released), and perhaps with the action of placing the stones, the builder could imbibe this power or energy and thereby make himself stronger.

As I mentioned in a previous article (Muller 1999), this particular feature bears a close similarity to a split boulder that I found in Montville, CT, which was also joined to the one next to it by a short stone fill (Fig. 8). I believe the same thought process is at work in both instances. This is not dissimilar to another feature at the Montville site, a split

boulder with a stone fill. The type of construction illustrated in Figures 7-9 is actually quite common throughout New England. It may be a narrow split which has been wedged up at one end with a single stone, or it may be a wide split such as we find in the illustrations above. Larry Harrop has recorded dozens of these various types in Rhode Island alone (Gallery).

From Feature C, the stone row ends at a large boulder with a rocking stone on top (Fig. 10). The rocking stone split off from the top of the boulder it is perched on and was turned upside down and placed in the depression. Until about seven or so years ago, the rocking stone was in place, but then one of the local residents decided to push it off, even though it must weigh at least a hundred pounds. It now sits on the ground at the base of the boulder, waiting for someone to put it back in place. Rocking stones were considered especially significant and powerful. The one at the Central Ridge site represents an example of a very large boulder that had very special attributes and attracted attention from far around. The one at the south end of the ridge might have been inspired by the one farther to the north, placing emphasis on a much smaller but important and significant site. The smaller stones placed below and in front of it might have been added to memorialize this site. We can see them from another angle in Figure 5.

Norman Muller,

March 2008